Note: This article was written before the start of the Coronavirus pandemic. If you are able to, please donate to Make the Road NY, one of NYC’s largest community organizations serving the working class, immigrants and people of color across the city. Make the Road NY’s Mutual Aid Bike Brigade is providing food pantry delivery to at-risk, elderly, or immunocompromised neighbors in Brooklyn and Queens.

2019 was an incredibly difficult year for cycling in New York City. 29 people riding bikes had been killed, almost three times as many as in all of 2018. We have lost so many dear people to senseless vehicular violence which shows no sign of slowing down. Meanwhile, the lack of response from the people responsible for ensuring safe infrastructure and traffic enforcement has been deafening. Ever since the killing of Robyn Hightman and the Washington Square Park die-in protest that followed, I’ve been feeling increasingly unsafe on a bicycle and have often opted not to ride instead. I’ve heard the same thing from many others, and some folks have stopped riding bikes altogether in fear of becoming yet another statistic.

The one refuge I’ve found over these last few months has been Mechanical Gardens, NYC’s only bike co-op. It is an amazing place, a community bike repair shop located in a church basement in Williamsburg. We welcome everyone and help them fix their bikes. It sounds pretty simple, but it is so much more. It’s a place with a focus on inclusiveness and solidarity, not just as something given, but as actions that need to be performed every single time someone new steps through the door. In the short time I’ve been volunteering with the co-op I’ve learned so much about teaching others with respect and care.

Wrenching at Mechanical Gardens has been a good way to focus my energy on something positive, and getting to know people who volunteer their time or drop in to get help has been incredibly rewarding. It was through Mechanical Gardens that I met Josh Bisker who originally introduced me to the bike co-op at the 2018 TransportationCamp NYC. Soon, Josh and I realized we had something else in common other than our love for teaching people how to repair bikes: both of us have a parent living with Multiple Sclerosis. Josh has been planning to do Bike MS, the National MS Society’s annual fundraiser ride, for many years and I jumped at the opportunity to join him! We started a Mechanical Gardens fundraiser which raised $3660!. There was only one problem — I had already booked a long overdue trip home in October, so I wouldn’t be able to join him for the 100 mile ride. We were eager to do the ride, so a decision was made: Josh would ride for his mom at BikeMS NYC up the 9W road in New Jersey, and I would ride for my dad independently in Croatia, joined by my partner Mandy.

Multiple Sclerosis

What is Multiple Sclerosis? MS is an unpredictable, disabling disease that destroys parts of the brain and central nervous system, disrupting the flow of information within the brain and to the body. The results are both cognitive and physical: extreme fatigue, problems with memory and concentration, blurred vision, loss of balance, dwindling mobility, and more. MS is different for everyone, and it’s still a fairly new medical field. That makes it all the more challenging to solve, but it also means that every dollar leads to new research that makes a serious difference in people’s lives.

The route

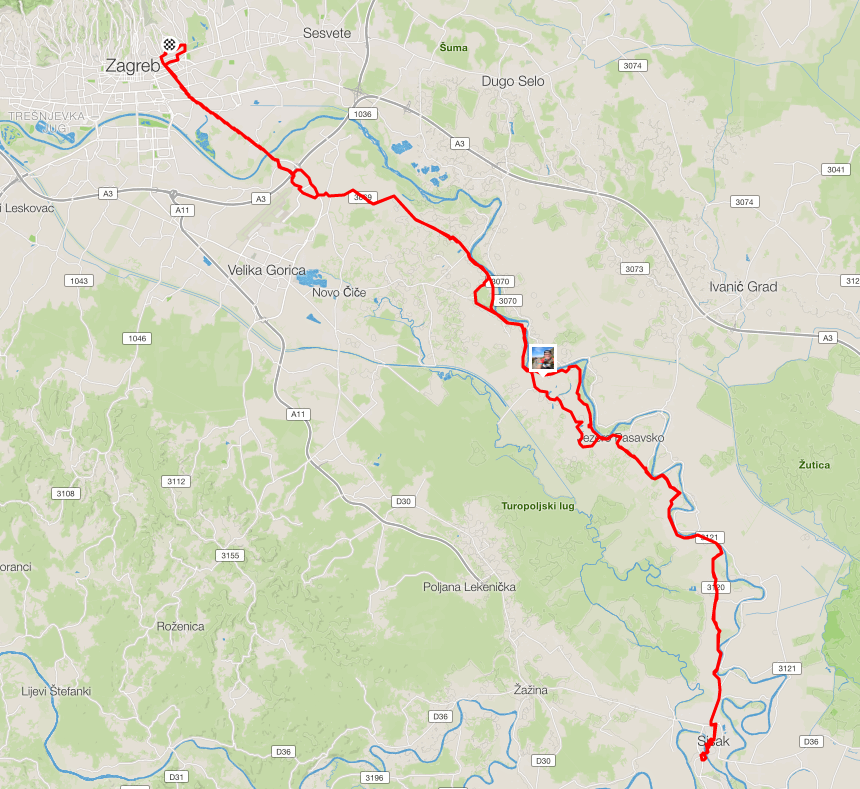

But where should we ride to? We wanted to do at least 100km, but the route had to be close to the city and preferably accessible by train so that we could get home easily in case of any bigger issues. We looked into doing a ride through Zagorje, the hilly region just North of Zagreb, but we got discouraged by the temporary closure of the local train line and the difficulty of getting out of the city without it. After some internet and Strava research, we eventually decided on Sisak – a smaller town just South East of our city.

The Bike

We didn’t travel to Croatia with our bikes, even though we really wanted to try flying with Bromptons. A friend of mine lent us a mid-2000s Scott hybrid for Mandy to ride, while I took my dad’s old Rog Senior. This bike was made in Slovenia and my dad rode it in the 80s. The bike then spent the next 20 years in a shed until I started restoring it about 10 years ago. I’ve added a Brooks B17 seat, switched out the wheels and tires, replaced the unfortunate cottered cranks and installed aero brake levers and modern side pull brakes. Finally, in preparation for this ride, I installed a new stem I got at Mechanical Gardens. It was lovely to have this bike connected to the co-op now! Rog bicycles have been made in Ljubljana since 1949. Rog made all sorts of bicycles, but their most famous model was Pony — a compact folding bike based on the Italian Graziella. They are still ubiquitous all over former Yugoslavia. Rog still makes bikes and their old factory has been transformed into a squat in Ljubljana, providing a space for community organizing, art and various other activities. It sounds similar to a co-op.

The ride

We left the house at 7:30am. It was a Sunday and the streets were completely empty. Even though it was late October, the temperature was unusually warm, the way October days have been feeling more like summer with each year. We took the almost direct route out of the city through Heinzelova and Radnička streets, starting at Kvatrić square. This route follows a wide avenue, but it includes a comfortable protected bike lane (technically located on the sidewalk but with good delineation and lots of space) and it goes on uninterrupted for 8km! While the route is comfortable, the street itself is not very pleasant. There are 6 car lanes with pretty fast traffic and almost no pedestrians — it mostly consists of decaying factory buildings that are slowly getting replaced with mid rise offices. The median includes a transit corridor for streetcar tracks which may get built one day (Zagreb has a large streetcar system but has built almost no new infrastructure in the last 30 years).

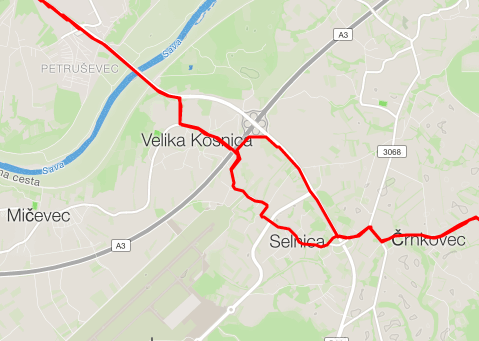

We soon reached the Domovinski bridge over the Sava river. The Sava goes through Ljubljana, then passes Zagreb and finally flows into the Danube in Belgrade — connecting three capitals of former Yugoslavia. The bike lane goes over the bridge, but the surface is full of bizarre craters — I’ve never seen this on a paved road before and it’s been like this for years. The bridge is followed by another gap in bike infrastructure. As it is about to cross the A3 motorway, the bike route disappears and we are redirected for almost 4km to a smaller overpass because the larger interchange doesn’t include access for bikes. This is extremely uncomfortable and it’s not marked at all — luckily I’ve ridden here before and knew how to cross the big motorway.

After the unpleasant detour we reach the bike route again and cross the new road to Zagreb airport (D430) which surprisingly also includes a protected bike lane! It’s a shame you have to navigate the secret overpass to get there. It was time to leave big roads and bike lanes behind. We crossed the D30, which loops around to Velika Gorica, and got onto county road 3069, heading East.

It’s crazy how quickly our surroundings changed! Within minutes we were surrounded by fields and passing through small villages. The road was narrow and there was barely any traffic.

The villages we passed through were small and picturesque. Early on we came upon a stork’s nest on a utility pole. Unfortunately, the storks had already left to Africa for the winter.

After a quick coffee break in Obed (population 51), we continued on South, now closely following the Sava river. After a little while, there was a turn towards the river and we figured we’d check out the bridge… To our surprise, there was no bridge and instead the crossing was served by a small cable ferry! Before the city expanded, ferries were common in Zagreb as well. The last one closed down in 1959.

As much as we wanted to cross the river and explore the Eastern shore of the Sava, we were on a tight schedule, and the cable ferry was on the wrong side. We continued South following the flood embankment on the West side. The narrow river road meanders through small villages, picturesque but uncomfortably empty. Many of the houses we passed by were old but well maintained. Others were boarded up and obviously empty. Curiously and quite wonderfully, very few cars passed us, and the people we came across either walked or rode bikes. We soon noticed that most of the people we passed were either very old, or very young.

In one of the towns by the river, Desno Trebarjevo (Trebarjevo on the right, across from Lijevo Trebarjevo, which is on the “left” side of the river, naturally), we noticed a monument to two men in front of a house. The monument honors Radić brothers who founded the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS), a major political party in the early 20th century. HSS is still around and currently holds 5 seats in the Croatian Parliament. Radić brothers are prominently featured in the Croatian education system, yet I never realized they were born in the small village of Desno Trebarjevo, population 396.

We passed other monuments too. Among many small churches and Catholic shrines, there was a significant number of monuments to the Narodnooslobodilačka borba (NOB) — the National Liberation Struggle of Yugoslav partisans during World War 2 against Nazis and local collaborators. During World War 2, this area was under control of the Nazi puppet state Nezavisna Država Hrvatska (NDH) which operated concentration camps, including Sisak children’s concentration camp (officially called “Shelter for Children Refugees”). It was a part of the larger Jasenovac concentration camp complex where thousands of Serbs, Jews, Roma and other victims were systematically murdered. After World War 2, Yugoslavia built monuments to the victims of fascism and partisan fighters all over the country, but during the violent disintegration of the Yugoslav federation in the 1990s, many of those monuments were purposefully destroyed or abandoned. The monuments we came across, however, were kept in reasonably good shape. They were small monuments, not the internet famous abstract “Spomeniks” that often appear on social media, drawing comparisons to science fiction and aliens. Their presence is a reminder of difficult and complex history, both in terms of atrocities they honor, and the more recent conflict that largely sought to erase them.

Biking through this beautiful region is incredibly conflicting. The beauty of nature is contrasted to the lack of people. We were less than an hour away from Zagreb, the economic and population center of Croatia, yet it felt like the only people still living here were the ones too old to move away. Croatia has been losing population rapidly, especially since it joined the EU. And I’m personally a part of this large group of younger people who no longer live in this country, coming back once or twice a year at most.

As we passed through one empty village after another, I could also not stop thinking about the many refugees less than 100km away in Bosnia, trying to cross into Croatia and continue West towards the rich EU countries like Germany. While most aren’t interested in staying here, the Croatian authorities have been violently and illegally pushing them back. “Push back” is the euphemistic term for illegally deporting people suspected of crossing the border without authorization. Croatian police catch them, beat them, steal their money and destroy their cell phones before they are transported to the border with Bosnia and forced to walk back through forests and mountains. These deportations are not documented, and the victims are not given opportunity to claim asylum. For years, Croatian authorities denied the practice of push back, until the former President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović openly confirmed it on Swiss TV last summer. The combined absurdity of witnessing empty villages and knowing that the police is “protecting” the border with violence is painful as much as it is absurd.

After some 3 and a half hours of riding, we enter Sisak. Sisak is not a large city (population: 50 000), so our first indication that we are now in the city is a simple welcome sign. Sisak is an ancient town. It was originally settled by the Illyrians and the Celts as early as 4th century B.C. and was then known as Segestica. The Romans attempted to take it over on few occasions before 35 B.C. when the Roman legions, led by Gaius Octavius (later known as Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire), captured the town and founded the Siscia military camp, which soon took over the whole settlement. Siscia became the capital of the Pannonia Savia province, and its city mint produced coins that were used all over the Roman Empire. In the 16th century, Sisak was part of the Habsburg Empire and site of 4 large battles between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy. While Sisak was occupied by the Ottomans on at least one occasion (after the 1593 battle), it was soon taken back by the Habsburgs and started to develop rapidly following the wind down of Ottoman wars in Europe in the early 18th century.

Sisak developed into a commercial and industrial center, first on the two rivers Kupa and Sava, and later on the railroad between Sisak and Zidani Most (Slovenia) which opened in 1862 as the first railroad in Croatia. In the 19th and early 20th century, Sisak specialized in iron works and oil industries. On June 22, 1941 the first detachment of the Yugoslav Partisans was established in the Brezovica forest near Sisak, starting the anti fascist resistance movement which eventually liberated Yugoslavia from the Nazi occupation. After the war, rapid industrialization of Sisak continued under socialism, with prominent metallurgic, oil, chemical and wood industries. At this point the population was rising rapidly, reaching 60 000 by 1991.

During the 1990s war in Croatia, Sisak was 10km away from the front line in Petrinja, and experienced shelling and mortar attacks from the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and insurgent Serbs. These attacks targeted industrial infrastructure, but they also damaged residential buildings and killed civilians. At the same time, 109 Serb civilians in Sisak were killed and disappeared during 1991 and 1992. Two former Croatian police officials involved in the disappearances were convicted of war crimes in the early 2010s by Croatian courts.

After the war and transition from socialism to capitalism, Sisak experienced rapid deindustrialization and depopulation. Many formerly state owned industries were privatized and closed down for good, causing huge unemployment. Sisak oil refinery, however, is still open and is currently in the process of transformation into a biorefinery. Sisak is in an extremely difficult position — the former industries had horrible environmental impact, but they provided the much needed jobs. Now most of the jobs are gone, but the pollution is still present.

We completed our ride on the shore of the Kupa river by the Old bridge and got some pizza. The riverfront was full of families having coffee, walking or biking. Sisak is going through some difficult times right now, but we could see that it’s a resilient town with a lot to offer. It persevered for over 2000 years, and it surely will make it through the current crisis. We had our lunch next to a group of teenage football players, getting pizza with their coach after the Sunday game. They were loud, the way teenage boys always are, but we enjoyed their company. It had been quite a lonely ride, and it was good to be in a crowded place!

On the ride back, we didn’t follow the Sava all the way, rather opting to pass through some of the bigger villages further West of the river. It was still warm, but the sun was getting low quickly since it was late October after all. We rode faster, trying to make up some time and get back to the city where our family waited for us at the “finish line” next to Maksimir park.

We passed the landmarks that were familiar to us by now, and luckily the roads remained almost as empty as they were in the morning. Eventually, we hit the A3 motorway and found the secret overpass — as soon as we crossed it we were back in the city of Zagreb! The last 10km were the hardest, and we were thankful for the protected bike route on the now busy Radnička corridor.

We made it back just in time! My parents and my sister welcomed us back at the entrance to Maksimir park. We covered a total 132km of distance, 28km shy of 100 miles, but it didn’t matter. We rode to raise funds for Multiple Sclerosis research, and together with Josh and Mechanical Gardens we raised over $3000! My dad has had the MS diagnosis for almost 10 years now, and living with this illness hasn’t been easy. It’s unpredictable, and there is so much we still don’t know about it — research is critical in finding the cure, but funds raised by Bike MS are also used to provide services to those living with MS — providing financial assistance, medical equipment, emotional care and much more.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this ride report. If you’re able to, I encourage you to donate to the National MS Society and Make the Road NY. If you’re interested in doing a bike ride in Croatia (once it becomes possible to travel internationally again!) and if have any questions, please reach out to me over email (vladimirvince at gmail dot com) or twitter (@mejs), I would be so very happy to help you plan your trip!