Note: this is the second article about my recent train journey through Bosnia and Herzegovina. Read the first article here.

With my route across BiH all planned out, I had to decide when to travel. It was necessary to schedule my train journey from Zagreb to Ploče, via Banja Luka and Sarajevo, before the end of August. The train from Sarajevo to Ploče runs only in the summer, and only on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. I scheduled the trip for Friday, August 29th. If everything went as planned, that would get me to Sarajevo on Saturday, August 30th and I would get on this summer’s last train to Ploče on Sunday, August 31st.

- Day one (Friday, August 29th):

- Train from Zagreb main station to Volinja (HŽPP) – 9:03am – 10:55am

- Bike from Volinja to Novi Grad (~23km). Cross into BiH at Novi Grad (formerly known as Bosanski Novi).

- Train from Novi Grad to Banja Luka (ŽRS) – 3:15pm – 5:20pm

- Train from Banja Luka to Doboj (ŽRS) 7:30pm – 9:38pm

- Taxi from Doboj to Maglaj (~25km)

- Hotel in Maglaj

- Train from Zagreb main station to Volinja (HŽPP) – 9:03am – 10:55am

- Day two (Thursday, August 30th):

- Train from Maglaj to Sarajevo (ŽFBH) 6:07am – 8:47am

- Hotel in Sarajevo

- Day three (Thursday, August 31st):

- Train from Sarajevo to Ploče 7:15am – 10:36am

Train 1: Zagreb main station to Volinja (HŽPP) – 9:03am – 10:55am

Friday morning I bike to Zagreb main station to catch the 9:03am service to Volinja. This was the least interesting part of my journey. I buy the 7,11€ ticket through the HŽPP app. This train to Volinja station on the Croatia – BiH border is a train making all local stops. The train is a standard HŽPP Končar 6112 EMV in the regional seating configuration (more seats vs. the commuter configuration with extra standing room). The main line to Sisak, originally built in 1862 as the Zidani most – Zagreb – Sisak railroad, is in good condition. It’s been recently renovated and the journey to Sisak is fast and positively uneventful. Past Sisak the train continues on to Sunja, where it turns southwest towards BiH and the Una river. The route includes a very scenic descent down to the Una from Hrvatska Kostajnica station. Very few passengers take the train all the way to Volinja, the border station on this line and the terminus of this service. At Volinja I assemble my bike and get ready for the 23km ride to Novi Grad (formerly Bosanski Novi) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I need to bike this distance because the railroad, which crosses the Una river into BiH past Volinja, hasn’t carried any passenger trains since 2016 (see the first article to learn more about this). The closest border crossing is in Kostajnica and the closest station with ŽRS service (Železnice Republike Srpske, the train company in the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina) is Dobrljin. However, Dobrljin is a very small village and I have 4 hours to wait until my next train to Banja Luka, so I decided to ride to Novi Grad instead.

I ride on the Croatian side of the river to Dvor (formerly Dvor na Uni), across the river from Novi Grad. I decided to take this road because it’s a bike route, and it is very pleasant to ride on since there’s very little traffic. The weather is good and the Una river is beautiful. As I bike through this scenic region, I see few people, mostly friendly retirees. This area saw horrible destruction in war, and 30 years later it is still economically depressed and many buildings haven’t been rebuilt. I pass many memorials: Croatian War of Independence, some WWII memorials, lots of plaques marking reconstruction investments over the years – USAID, the German government, the European Union.

Even though I’m starting this trip in Croatia, significantly richer than Bosnia and Herzegovina and flush with EU funding, I’m already surrounded by the root cause of why this trip is so long and difficult in 2025 – the devastating and lingering effects of war, 30 years on. It’s not just the ruins, it’s the absence of people, the visceral feeling that there used to be a lot more life here. As I ride, I get passed by the police patrolling this area, trying to stop those even less fortunate from crossing the Schengen border into the European Union. This area is once again the borderlands, strangely reverting the Una river back to the role it served during the centuries long period when it was a part of the Military Frontier, a fortified area between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire under the direct control of the Habsburg Military.

I cross the border on the bridge between Dvor and Novi Grad. I almost cause an incident because there’s no obvious place to stop on the Bosnian side, and I don’t see the border guard standing across the road. He yells at me to stop so I bike back and apologize. There’s no other traffic so I’m let in without further issues.

I have a few hours until my train to Banja Luka departs, so I bike around. There’s more life here, cafes are open and there’s people walking around. Novi Grad isn’t large. In the pre-war days, when it was still called Bosanski Novi, it used to be a small industrial center with a developed textile industry built around the Sana factory, named after the Sana river which flows into the Una at Novi Grad. I visit the Zavičajni muzej in the old town hall. This beautiful building was constructed in the early days of the short Austro-Hungarian rule of Bosnia (1878–1918). The small museum features local artifacts, examples of traditional dress, and an exhibition about Milan Karanović, an early 20th century ethnographer.

As soon as you enter Novi Grad you can immediately sense the post-conflict political division of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The only places featuring any symbols of the state of BiH are the border crossing and the police station. Everywhere else you see flags and other symbols of the federal entity Republika Srpska. I walk down the beautiful quay along the Una, passing by the ruins of the old Sana factory. A plaque about river boats features the tourism slogan of Republika Srpska: “Nothing much but much more”. Further up the river, ruins of an old riverside hotel. The structure is eerie, but appears to be structurally intact. A large yellow “disco” sign suggests a not so distant past when this place was full of life. In 1992 however, Una Hotel was a site of torture and murder. I don’t spend a lot of time there, I go back to the Zavičajni muzej and get a coffee at a riverside bar with a view of the Una and the border bridge.

I watch the border bridge with its big blue “EU” sign. I can cross this bridge freely, briefly flashing my ID. Meanwhile, for countless others fleeing violence and poverty, crossing incredible distances trying to reach safety in the European Union, this bridge is a dangerous obstacle. They attempt to cross the river elsewhere, risking drowning, beatings and violent “push backs” (euphemism for illegal deportations) if caught. The historical legacy of this area as a centuries old borderlands, and more recently its legacy of war and subsequent instances of ethnic cleansing, is not lost on me. The incredible natural beauty coexists quietly with the heavy legacy of history. Meanwhile, I do not wish to exoticize the past nor the present. There’s nothing inherently violent about this river. The Una became an important line on the map centuries ago and it stubbornly maintains this violent border role to this day, the Yugoslav period seemingly a short aberration from this permanent state.

Train 2: Novi Grad to Banja Luka (ŽRS) – 3:15pm – 5:20pm

Before biking to Novi Grad station, I stop by an ATM to take out some Bosnian currency (BAM = Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark). BAM roughly converts to about 0.5€. I get charged a pretty hefty fee by the UniCredit Bank ATM, but I prefer to take the hit rather than deal with sketchy currency exchange offices. I also stop by the grocery store, Market AS, and buy some food for the 2 hour trip to Banja Luka. Novi Grad station is in decent shape. A large sign commemorates the 30th anniversary of Željeznice Republike Srpske. In 2025, this station sees 4 pairs of passenger trains a day, all going to or from Banja Luka. In the pre-war days, this place was much busier. Bosanski Novi used to be a junction for trains going north towards Zagreb, trains going south towards Bihać and Split, and those going east towards Banja Luka and eventually Sarajevo. No regular trains to Split have passed here in 35 years, while service to Bihać (located in Federacija BiH) only lasted 2 years from 2018 to 2020, before getting cancelled again at the start of the pandemic.

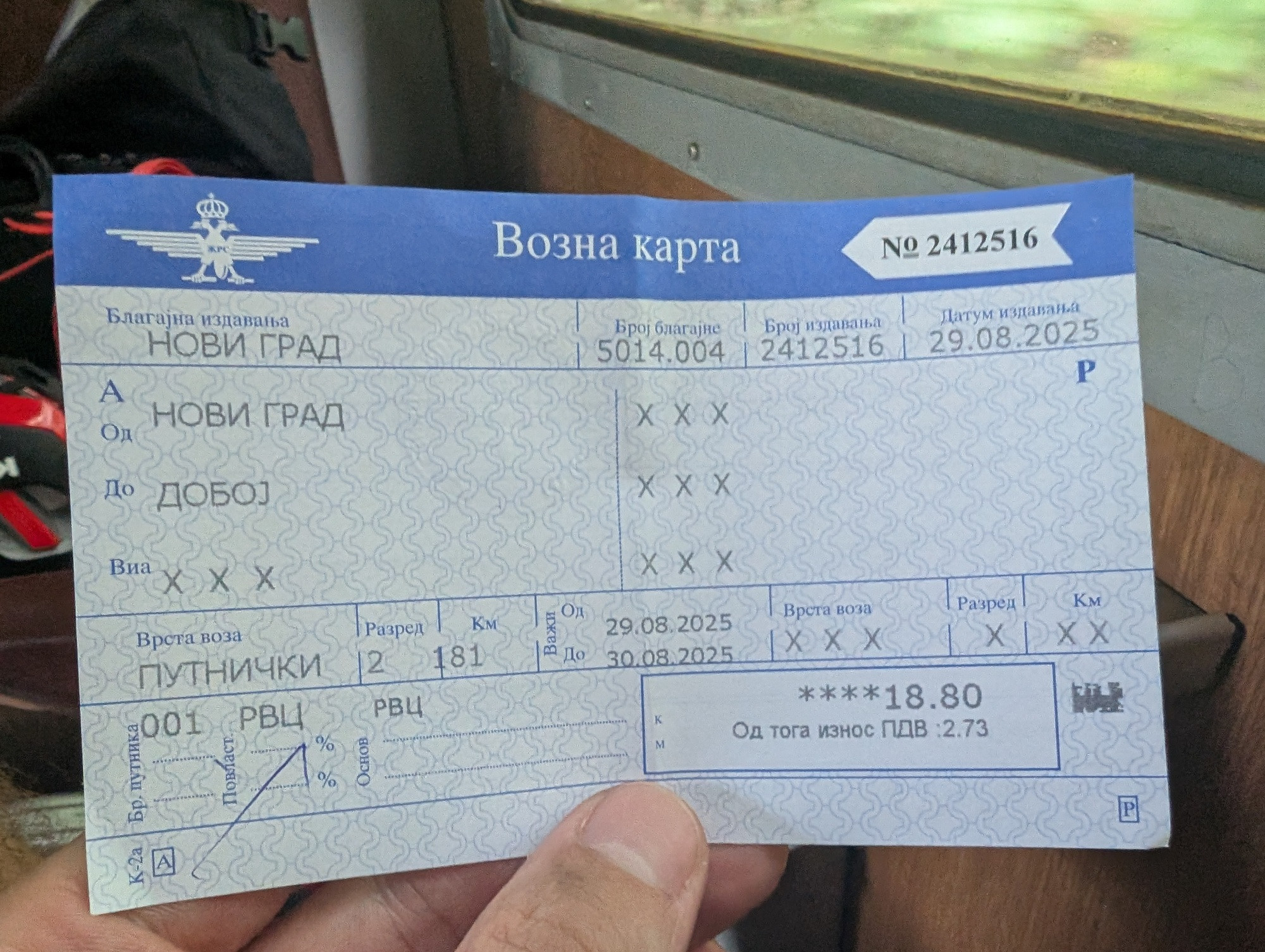

There’s a ticket office at this station so I go and buy a ticket all the way to Doboj, with a change in Banja Luka. The ticket seller is shocked that I’m taking such a long trip (178km). She asks multiple times if I know that I need to wait in Banja Luka for 2 hours before continuing on to Doboj. I assure her I know what I’m doing and she sells me a combined ticket for 18.80 BAM. I pay with cash (I do not see a card terminal) and she prints the ticket using a Windows XP computer with a CRT monitor, and prints it out on a dot matrix printer. Neat.

A handful of passengers wait for the train. There’s a large war memorial at the station, commemorating the “Obrambeno-otadžbinski rat” as the Bosnian War is referred to in Republika Srpska. People at the station are talking about the train line. One passenger mentions that he’s never been to Zagreb. “Really?”, asks someone. “Well, not since the war”, he answers. Zagreb is less than a hundred miles away.

Our train arrives on time. A Yugoslav built Swedish ASEA locomotive pulls a single carriage. There’s so few of us on this train that we can all take private compartments. The compartment is dirty, but very comfortable. There are cigarette butts around. Somebody had a very comfortable ride here earlier! Luckily, the window can open. I discover how it’s held open – with a tiny Bosnian pfennig coin. This trick will come in handy later. The train follows the Sana river until Prijedor. The ride is comfortable. The train fills up a bit at Prijedor and I get some compartment buddies. A student going home to Banja Luka, and an older woman traveling to a village between Prijedor and Banja Luka. The ride isn’t particularly scenic, but we hit 70 km/h on some sections. The railroad is single track, but it is electrified. It’s in completely usable condition.

The train slows down at road crossings, many of which are manually operated and manned by railroad staff. As we get closer to Banja Luka we pass a few automated crossings. We get to Banja Luka with less than a 5 minute delay. There’s no other trains at Banja Luka, but we see many old train cars parked to the side.

Banja Luka station is an enormous modernist station with some post modern features. The station was designed by Živorad Janković, who designed a number of prominent public buildings in Yugoslavia including the Skenderija sports center in Sarajevo. This is a relatively new station, with construction starting in 1983. Construction was interrupted by the war and the station was finally completed in 2002. The station is now mostly empty, as Banja Luka sees only 8 pairs of passenger trains a day, with no international services and no trains going to Federacija BiH.

My Brompton comes in handy since the train station is pretty far from the city center. Banja Luka is surprisingly pleasant for biking, with lots of good quality bike lanes. I bike towards the city center. There’s lots of construction going on, with lots of residential and office buildings under construction. Billboards advertise the Belgrade Expo and the Serbian basketball team, alongside the former president of Republika Srpska. In late August 2025 the position of the President of Republika Srpska is technically vacant, but this is disputed by the former president Milorad Dodik, whose face is on posters all over Banja Luka. I ride through the city center and pass by the Kastel Fortress, the medieval fort on the bank of the Vrbas river. It’s getting late, so I don’t get to visit the fortress.

I get dinner at Pod lipom, a ćevabdžinica near the Kastel fort. I get some banjalučki ćevapi with kajmak, a local delicacy, and some non alcoholic beer. The food is good and affordable, and outside seating is pleasantly located under a lime tree, which the restaurant is named after.

Train 3: Banja Luka to Doboj (ŽRS) 7:30pm – 9:38pm

Soon it is time to return to the station and catch my train to Doboj. There are now two trains at the station, the 7:20pm towards Novi Grad and the 7:30pm towards Doboj. Both trains are pulled by ASEA locomotives and each pulls two passenger cars. There’s at least a few dozen passengers getting on the two trains. As we’re getting on the train, you can hear a crowd singing folk songs, accompanied by an accordion. The party is invisible, but their celebration adds to the ambiance.

With the music playing, we continue on the last train leg of today’s journey across BiH. The train cars seem a bit newer, and they are definitely cleaner than the one on the train from Novi Grad. It gets dark pretty quickly and it starts to rain. It’s very hot and stuffy inside the train, but I’ve figured out how to prop the window with a coin myself. I use a 5 cent coin and the window stays open.

The railroad we take to Doboj was built by 70 000 Yugoslav youths in 1951, in one of the last major youth work actions. The 93km long railroad connects Banja Luka with Sarajevo via Doboj. Soon it’s completely dark. We pass a lot of stations in surprisingly good condition. Other notable landmarks include a brightly lit up gambling outpost and an enormous coal power plant in Stanari.

I spend the ride reading the 1990/1991 Yugoslav railways timetable. Looking at the basic performance of this railroad, it isn’t all that bad for local service. The run time between Banja Luka and Doboj is still within 15 minutes of the pre-war local trains. But local service is the only service still running on this railroad. 35 years ago you could travel from Doboj to Stuttgart. In 2025 you can reach Novi Grad and that will take you half a day.

After 2 hours we reach Doboj with minimal delay. Doboj station is in decent shape, like most other stations we passed. The railroad splits here. To the north it goes on to Šamac and connects to the Zagreb – Belgrade main line at Strizivojna-Vrpolje, of the Murder on the Orient Express fame. To the east it continues to Tuzla and Zvornik, and to the south it goes to Sarajevo. No passengers trains go to any of those places anymore, so I need to get off at Doboj since this is the last stop on this train. It’s pouring outside, but I have a taxi waiting for me. The taxi will take me to Maglaj, where I will catch the ŽFBH (Željeznice Federacije Bosne i Hercegovine) train to Sarajevo in the morning. I booked the ride to Maglaj via email, and the driver already knows where we’re going.

We drive on the west side of the Bosna river, while the railroad is on the east side. The driver tells me that there’s another road on the east side that would be pleasant to bike on, since all the heavy traffic takes the west side road, the M-17 single lane highway to Sarajevo. Once we reach Maglaj, he asks for my help finding the hotel, since he doesn’t come here much. We have now left Republika Srpska and reached Federacija BiH. The total for the drive is 37 BAM, more expensive than the train from Novi Grad but completely reasonable for a 25km taxi drive.

I check into my hotel. I booked the place via Booking.com, but I couldn’t pay online. Luckily I can pay by card. The total is 118 BAM – more than I would have liked, but the hotel is very nice. There are only two hotels in Maglaj, and this was the cheaper one. The receptionist is a young guy and we have a nice conversation. I tell him I’m on my way to Ploče and he tells me he would like to go to the seaside. He won’t make it this year. I tell him I’d love to see Maglaj in the daytime, but I have to leave very early in the morning. He tells me he’d also like to see Zagreb one day, but he hasn’t had the opportunity yet. He wishes me luck on my journey and I wish him luck in life. As I crash in my room, I feel great sadness that in 2025 reaching the Adriatic coast or Zagreb is so difficult for a young Bosnian man working in Maglaj.