Note: this article was originally written for the Club de Aventuras AD magazine. You can read it in Spanish translation starting at page 68 of Issue 60 of CAAD.

Home computing in Yugoslavia, a country that no longer exists, was quite interesting in the 1980s. The geopolitically unique position of this socialist country during the Cold War produced a unique situation in terms of access to computers and technology. Yugoslavia was one of the leading countries of the nonaligned movement, a group of countries primarily from what we now call the Global South, who sought a “third way” path between the capitalist West and the communist Eastern bloc countries. This meant that the Yugoslavs had relatively relaxed access to travel to both the East and the West, and to import and export technologies to both.

While this didn’t mean that the Yugoslav could as easily obtain computers as people in Western Europe (look up the story of the Galaksija DIY computer), they still mostly used American and British machines like the Commodore 64 and the ZX Spectrum. Early in the 80s they had to find creative solutions to import them (ie. smuggle them through customs), but by 1985 such computers were being sold in Yugoslavia directly. Sinclair even partnered with a local company called Iskra to assemble ZX Spectrums in Yugoslavia. By late 1984 it was estimated that there were between 20,000 – 30,000 ZX Spectrums in Yugoslavia, almost all of which would have been brought in from abroad.

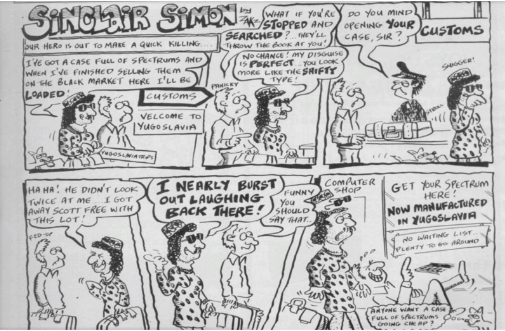

Smuggling was a national sport – one of the perks of Yugoslavia’s good relations with the West was easy access to countries like Austria and Italy, where cities close to the border (primarily Trieste in Italy and Graz in Austria) became shopping meccas for the Yugoslavs looking to purchase goods that were difficult to find locally. The catch was that while they were free to travel back and forth, they were limited to importing only 50 Deutsche Marks worth of goods per trip, a limitation that made even the cheapest microcomputers technically illegal to bring with you. Despite this, enforcement was relatively lax, as you can see in the comic strip above, published in November 1984 just as ZX Spectrums started to get sold in Yugoslavia.

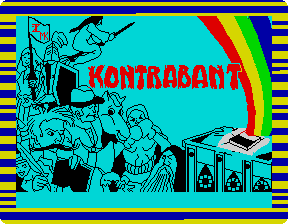

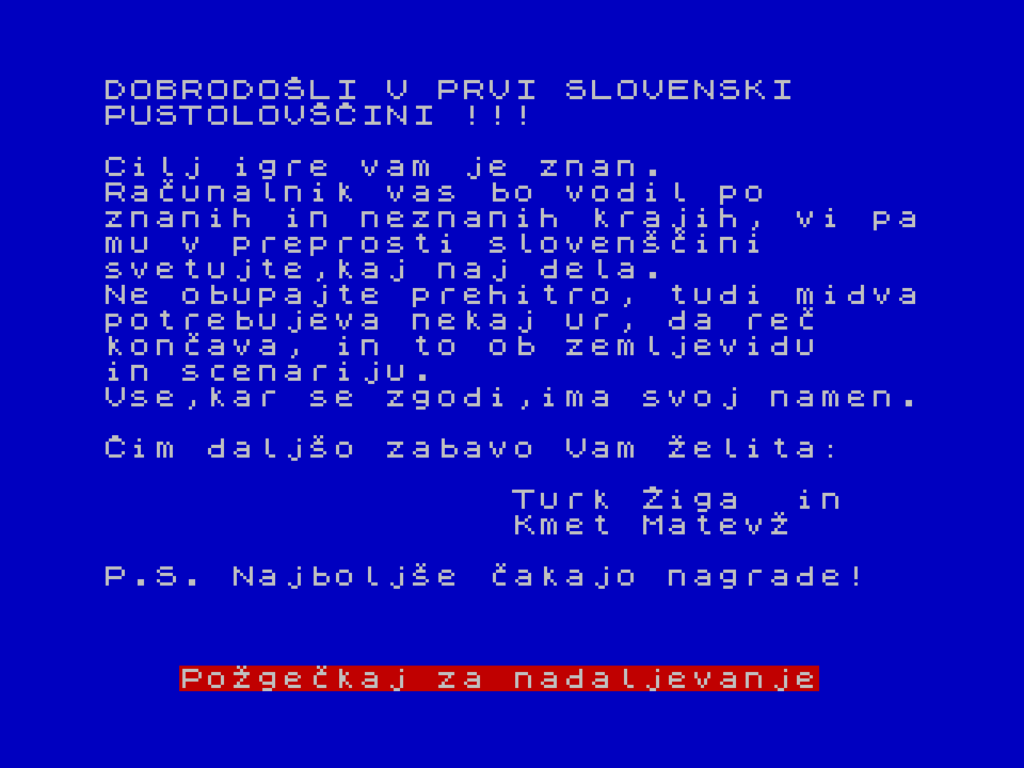

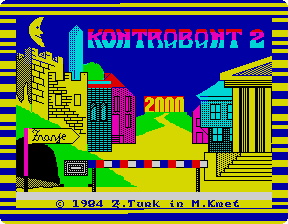

It’s primarily the experience of having to find “creative solutions” to get a computer that inspired one of the first Yugoslav adventure games – Kontrabant (“Contraband”). This game, written by a pair of Slovene students and published by the Radio Študent youth radio station, has the player travel around the country (and beyond!) to collect parts and ultimately smuggle a computer. The game was (appropriately) released for the ZX Spectrum at the time when virtually all ZX Spectrums would have been obtained in a similarly dubious fashion.

The game sets the scene: Life is boring – the TV shows the same old movies, nothing interesting is on the radio, the news and magazines are boring. The only solution is to find a TV, a tape deck and a microcomputer. You get out of the house and find yourself in the middle of Ljubljana. A man puts a badge on you that says “Attention – Beginner Adventurer”. From this point on your adventure begins. Through the course of the game you collect items and meet characters looking for different goods. Some of the characters are famous smugglers from Slovene history who help you on your way. You travel across Yugoslavia exchanging different goods and obtaining items you’ll need to assemble your computer – you’ll need a TV and a tape deck, but you’ll also need a picture for your passport so that you can leave the country. The game is simple, but it requires a lot of contextual knowledge of both contemporary Yugoslav culture, as well as Slovene myths and historical characters. It’s also quite funny and random at times – for example, one of the items you obtain in Austria is a porno magazine, which you then exchange for some other goods. You continue collecting items until you finally assemble a computer!

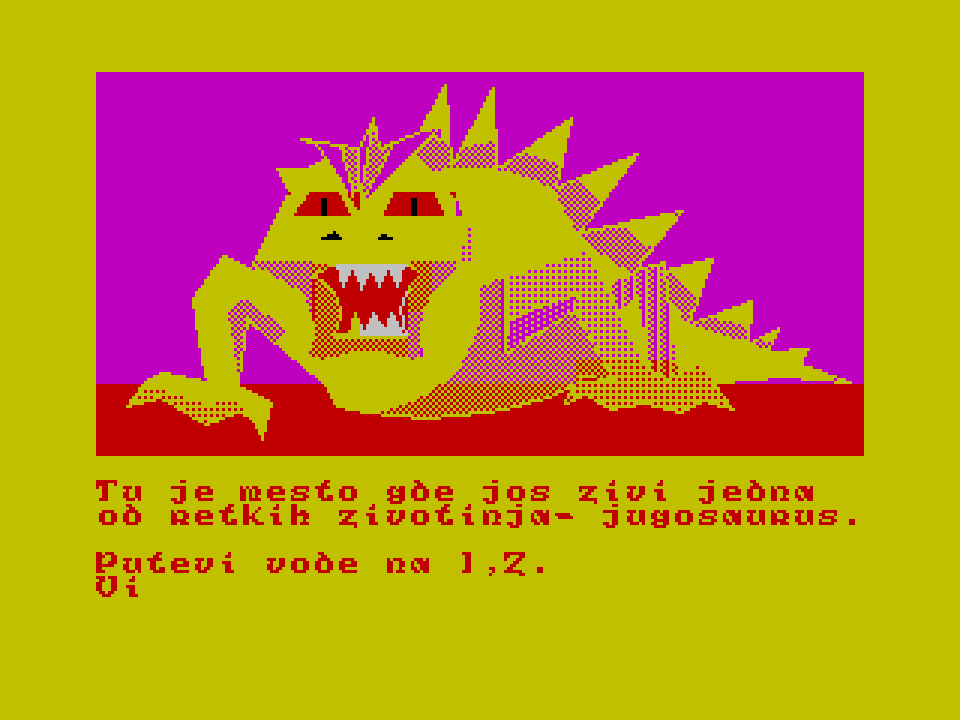

This game was quite successful, and it spawned a sequel – Kontrabant 2. Unlike the first game, which only features text, Kontrabant had some nicely drawn images. Thematically, it moves away from the “smuggle a computer” goal and instead takes the character on another tour de force journey across Yugoslavia, encountering monsters and other challenges as you try to make your way to the year 2000 and to the amazing computers of the future. Like the first game, there is a political subtext and critique of social and economic conditions in 1980s Yugoslavia. The tape also features a couple of punk rock songs by the “Kontra Band”, thematically relevant to the game.

“Yugosaurus” monster in Kontrabant 2

Another popular Yugoslav adventure game was Vruće ljetovanje (Hot Summer) where you need to get your family over to the coast for vacation. You keep running into increasingly difficult issues and challenges. You start by waking up and you need to get some breakfast. This simple task teaches you the game mechanics, because the game is timed and you need to eat and rest (or you will die!). Your character, a father called Srećko, has to get money and food for the vacation, then when he tries to book a trip he finds out that all the spots are taken. Luckily, he bribes the travel agency clerk and books the vacation.

The game is interspersed with tasks and situations typical of the Yugoslav working class life in the 80s, the challenges caused by rapid inflation, low level corruption at every step and other daily difficulties. When you finally get to the coast things get really interesting. A certain Maja leaves a message for you to meet her at the nudist beach. She had her ring stolen and asks for your help retrieving it – turns out a group of gamblers is staying at the hotel with a load of stolen goods. You decide to help Maja, but you also need to make sure your wife doesn’t think you’re cheating. Through a series of twists and turns, you manage to recover Maja’s ring and other jewelery, and as a reward you get another week on the coast with your family.

Due to complex mechanics with time, hunger and rest variables, Vruće ljetovanje was arguably the most difficult Yugoslav adventure game. Additionally, the syntax could get incredibly complex, with sentences of up to 10 words! Very few players would have finished this game, but its highest value is in its historical and local context. Players familiar with daily life in Yugoslavia will recognize the challenges of the time, and local references to locations, companies and pop culture references are integrated with the gameplay seamlessly. Additionally, the illustrations used in the game are very well done. They were drawn by Igor Kordej, a comic book artist who would later on go to produce work for both Marvel Comics and Dark Horse Comics.

In addition to the Kontrabant series and Vruće ljetovanje, there were maybe a few dozen other domestically produced Yugoslav adventure games. Like with other software and games at the time, due to easy access to (most often pirated) foreign titles the domestic production was relatively limited. A lot of homebrew adventures were simple crime mysteries, with noir elements. While most of these other games were pretty simple, a few more interesting ones include Bajke (“Tales”), based on classic Slovenian children’s tales, XIV (“14th”) series about adventures in Belgrade’s XIV Gymnasium and Na Balkanu ništa novo (“Nothing new in the Balkans”). This last one is particularly interesting, as it’s one of the final Yugoslav games before the break up of the country. It explicitly deals with the then brewing political conflict, featuring many real life characters, some of whom would become leading figures of the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Domestic adventure games in Yugoslavia represented a relatively minor part of computer gaming experience, but they were a fascinating platform for experimenting with both alternative forms of narrative, but also as another avenue for political expression. Both of the featured games give us great insight into daily life of Yugoslavs in the 1980s in a way that other games produced locally do not – it’s specifically through the focus on the narrative that the local context is centered.